A new study found so-called “forever” chemicals in stain-resistant school uniforms. Scientists don’t fully understand the health risks of these chemicals, which are known collectively as PFAS. But data suggest some of them are potentially toxic. And that’s concerning because lots of kids wear uniforms. Roughly one-fifth of U.S. public schools require them. Many private-school students wear uniforms, too.

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl (POL-ee-flor-uh-AL-kul) substances. There are roughly 9,000 different versions of these. All have chains of carbon atoms bonded to fluorine (plus other groups of atoms). These substances are used in nonstick coatings, fire suppressants, stain- and water-resistant fabrics and more.

“They’re called ‘forever’ chemicals,” explains Marta Venier, because they don’t break down in nature. Venier works as an environmental chemist at Indiana University in Bloomington. These compounds show up in water, air and soil around the world, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) notes.

Scientists worry especially about children’s exposures to such chemicals. Young bodies that are still developing might be especially vulnerable to them. And some of the chemicals can build up in the body. Studies have linked some PFAS to greater risks for asthma, problems with vaccine effectiveness, high body weight, high cholesterol, kidney problems and more.

“These chemicals can go through the skin,” Venier says. Researchers don’t yet know how much gets through and what levels cause problems. “But there is a concern,” she says.

PFAS are widely used in clothes

Venier’s group bought 72 items of children’s clothing in Canada and the United States. These included school uniforms and outdoor wear. There were also sweatshirts, swimwear, bibs, shoes and more. Most items were advertised as resisting stains, water or wrinkles.

Those traits often are a clue to fabrics with PFAS, says Laurel Schaider. She’s an environmental chemist with the Silent Spring Institute in Newton, Mass. She did not work on the new study. But research that her group published last May found that fabrics may contain PFAS even when their labels didn’t list it. This could be true, they found, even if items were sold as “green” or “nontoxic.”

Venier’s group found fluorine in about two-thirds of the 72 items tested. All 26 stain-resistant uniforms they tested had PFAS. Nineteen of these 26 — or 73 percent — had levels of 1,000 parts per million or more. Those high levels suggest that companies used PFAS on purpose (it hadn’t shown up by accident). And because the tests that were used could not detect low levels of fluorine, they may have even missed PFAS in some fabrics.

Scientists say: Chemical

The team used a different method to look for 49 specific PFAS chemicals in all items in which the tests had turned up fluorine. The group also ran those tests on 10 other items. PFAS showed up in all those products — even the ones that didn’t initially test positive for fluorine, says Chunjie Xia. He’s the study’s lead author. Like Venier, he works at Indiana University.

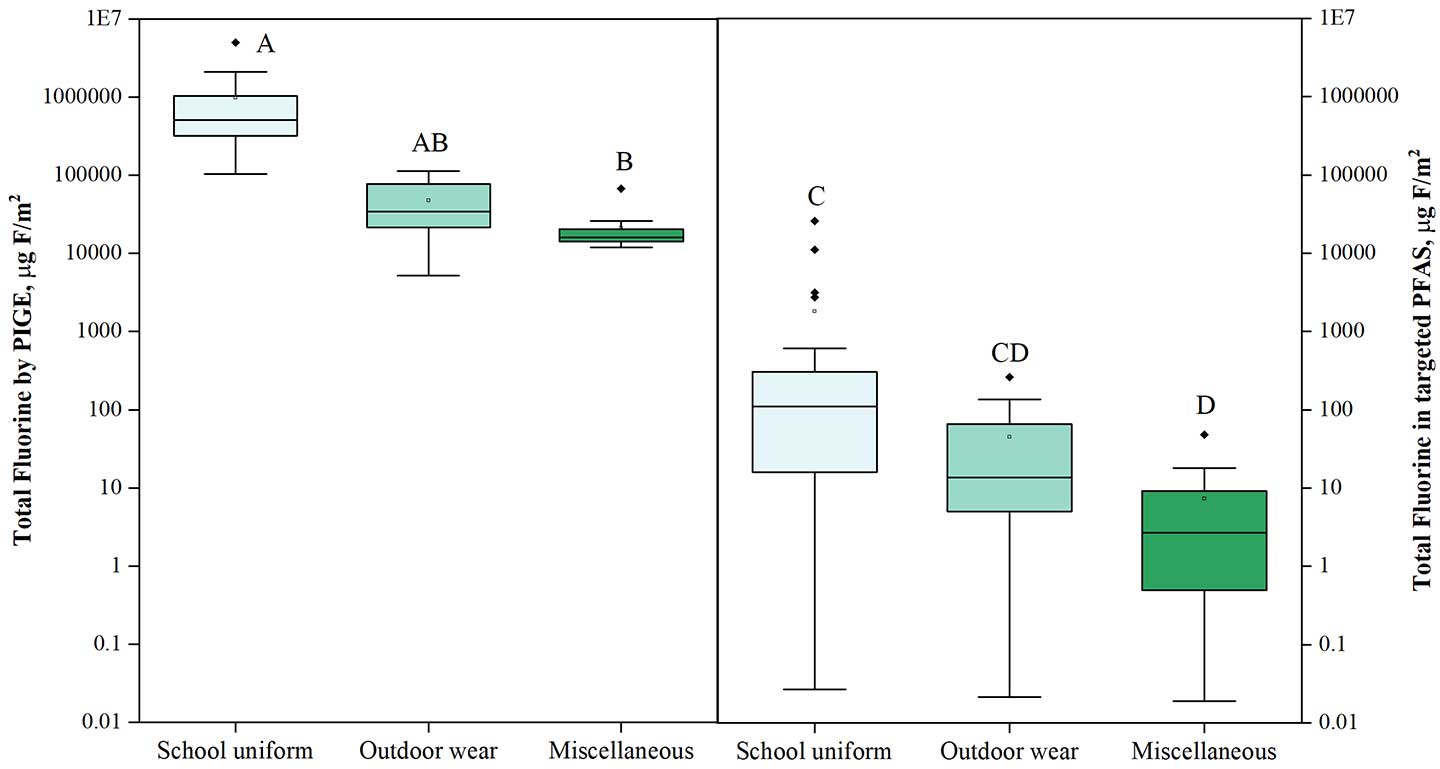

School uniforms had the highest median levels of fluorine. (The median is the midpoint value; half of the other values are above it and half are below.) Results from the tests for specific PFAS chemicals showed a similar trend. Uniforms that were all or mostly cotton tended to have higher PFAS levels than did those made from other fabrics. Cotton may need more treatment to make it stain-resistant, Venier suggests.

The overall levels in school uniforms were similar to those in outerwear (such as coats), the authors report. But students wear school uniforms against their skin and often for up to 10 hours a day. So, a child’s exposure from a uniform would likely be higher than from a jacket. The researchers shared their findings in the Oct. 4 Environmental Science & Technology.

“I was really surprised at the number and amounts of PFAS in all of these different textile articles,” says Jamie DeWitt. She’s an environmental toxicologist at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. She did not take part in the new work on PFAS by either Venier’s or Schaider’s groups. Some data also puzzled her. It didn’t make sense for PFAS to be in some of the items, she says, such as bibs. The point of a bib is to save other clothes from stains.

What can you do?

“Don’t panic,” DeWitt says. There’s much that researchers still don’t know about PFAS and the effect of exposures from clothes. But researchers do know stain resistance isn’t essential in a school uniform. Stain-resistant clothes don’t make kids healthier or safer, she explains. Nor do they improve kids’ ability to learn. And there are other ways to deal with stains, such as dark colors or more washing.

If people must wear a stain-resistant uniform, buy it used, Venier suggests. And wash it often. “With every washing cycle,” she notes, “you wash away a little bit of the PFAS.” Of course, chemicals that leave clothes in the wash go into the water, dryer lint or the air, she adds. So they will be released into the environment, she says, where they might still cause harm.

Meanwhile, school uniforms are “just one factor that may contribute overall to children’s PFAS exposure,” Schaider notes. Over concern about PFAS health risks, the U.S. EPA announced last June that it plans to regulate PFAS in drinking water. In fact, these chemicals are so widely used that most Americans likely have some of them in their blood, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

Many companies are pledging to stop making or selling items with PFAS, Schaider notes. Proposed state laws also might have an impact.

You can speak out too. Says DeWitt: “Don’t underestimate the power of your voice as a consumer.”