In parts of the western United States, sometimes the sky looks gray and the sun is hidden from view. Not because of clouds but because of wildfire smoke. That smoke contains tiny particles, which are harmful to health. Now, researchers have found that exposure to such pollution has grown in the United States over the past decade as wildfires have gotten bigger and more common.

“There’s so many health effects from particulate matter,” or PM, says Marissa Childs. An environmental health researcher, she works at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. Especially concerning are really small particles, called PM2.5. These are smaller than 2.5 micrometers. That’s about one-thirty-fifth the thickness of a sheet of paper.

Health risks from such particles include asthma and shorter lifespans. Childs and her colleagues wanted to better understand the health effects of PM2.5 from wildfire smoke. But first, they needed to know how much exposure to it people in different places were having. So, the researchers set out to map this pollution.

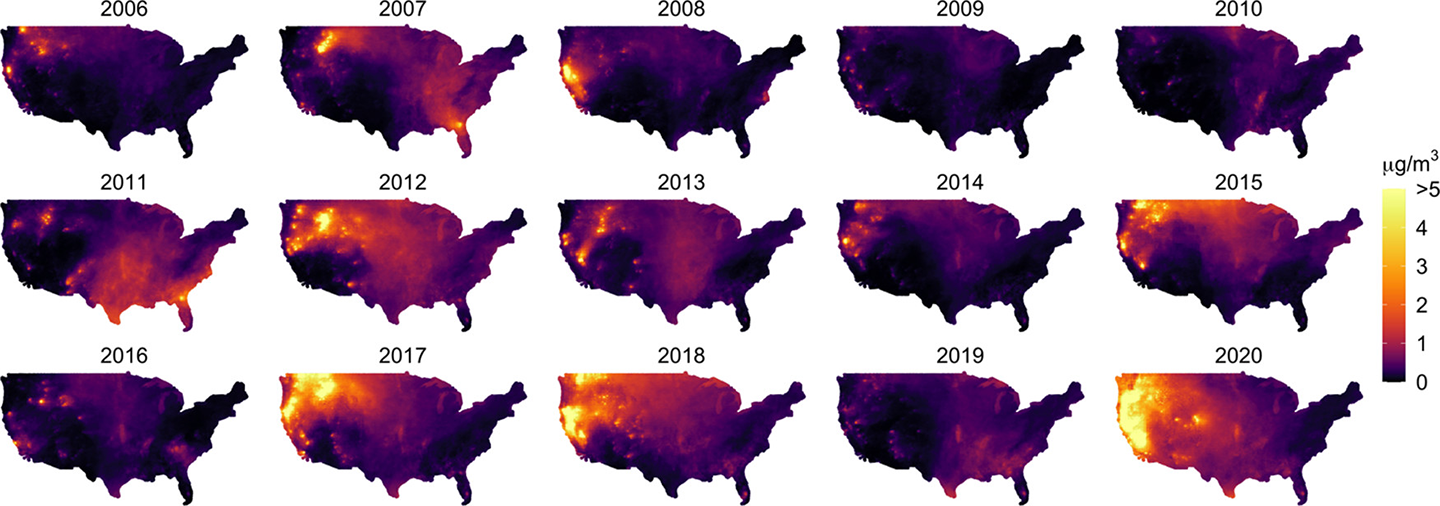

First, they gathered data on PM2.5 levels from about 2,000 air-monitoring stations across the United States. Satellite images of plumes of wildfire smoke allowed the researchers to estimate how much of the PM2.5 in each place appeared to come from this smoke.

Vast areas, however, have no monitoring stations. To estimate smoke PM2.5 in those places, Child’s team started with the satellite images of smoke plumes. Then they trained a computer model to calculate smoke PM2.5 levels, in part, based on those images. The model considered many factors, including wind direction and speeds, temperature and distance to the fire.

This allowed the team to estimate the daily PM2.5 from smoke to which people across the continental United States were exposed during 2006 to 2020. (The map did not include Alaska or Hawaii.)

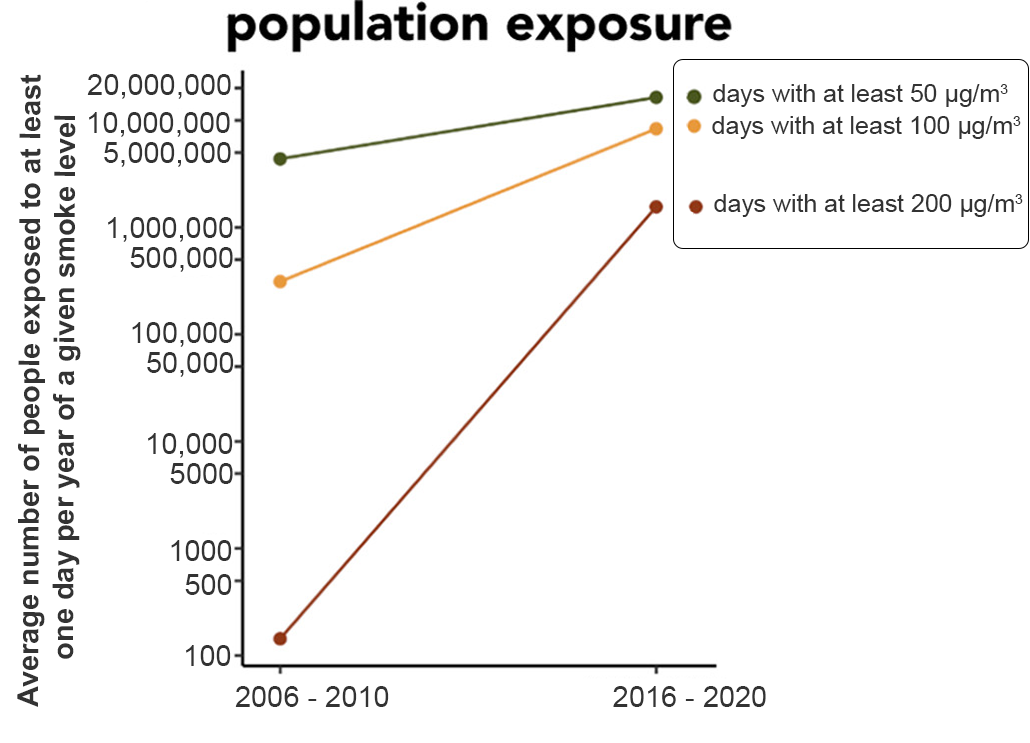

“We especially see a really large increase in the number of extreme days with high pollution levels,” says Childs. In 2020 alone, 25 million people experienced at least one day where PM2.5 levels were over 100 micrograms per cubic meter. On days with such high pollution, people in affected areas shouldn’t be spending a lot of time outside.

The researchers shared their findings in the October 4 Environmental Science & Technology.

logarithmic scale. That scale more easily shows the huge range of smoke exposure.

Researchers calculated the number of people exposed to at least one day a year at these levels. They averaged those results from 2006 to 2010. They also averaged the results for 2016 to 2020. The change across the last decade is the later years’ value minus the earlier years’ value.