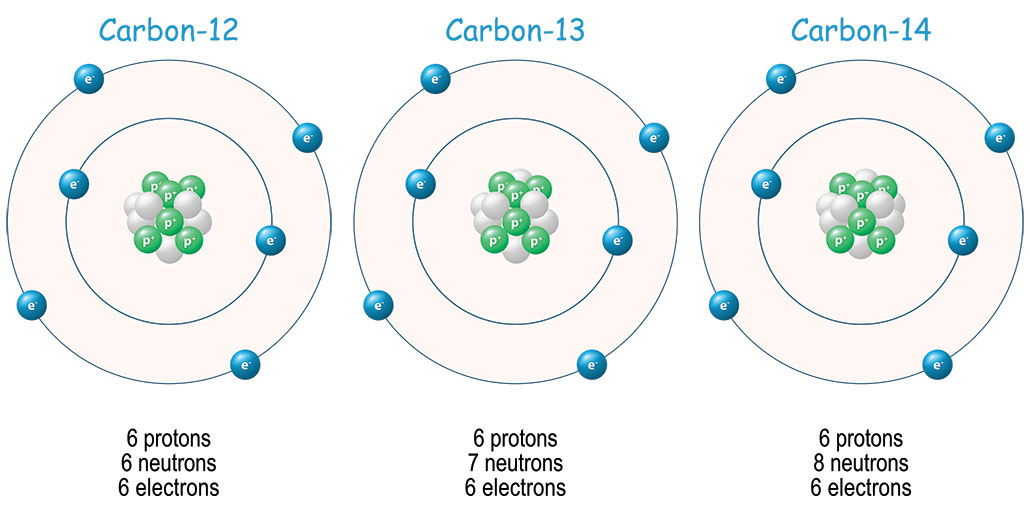

Carbon is the basis of life on Earth; it’s in the cells of every living thing. This element comes in several forms, or isotopes. Most of it will be the stable form: carbon-12, which is non-radioactive. But some of it is carbon-14. This isotope is unstable, meaning it decays — morphs into another element over time. Scientists have been able to use that decay to figure out the age of once-living things up to 55,000 years old. But for modern artifacts, the use of this carbon dating has become a little less reliable. The reason is society’s rampant burning of fossil fuels.

Explainer: Radiation and radioactive decay

That’s the findings of an international team of scientists. They described the problem July 19 in the journal Nature.

Scientists can use several different elements to date objects from the past. One widely used dating technique relies on the clock-like decay of carbon-14. While organisms are alive, the carbon cycle ensures they all have about the same level of carbon-14 in their cells. After death, amounts of carbon-14 gradually start to fall as the radioactive atoms in their once-living tissues begin to decay. It happens very slowly. It takes 5,730 years for their levels to drop by 50 percent.

Scientists can figure out about how old a material is based on how much of that carbon-14 is left.

At first, this technique was useful only for dating fairly old artifacts — items maybe 10,000 to 50,000 years old. It didn’t work well on recent remains. Not enough of their carbon-14 had decayed to be easily measured.

Explainer: Radioactive dating helps solve mysteries

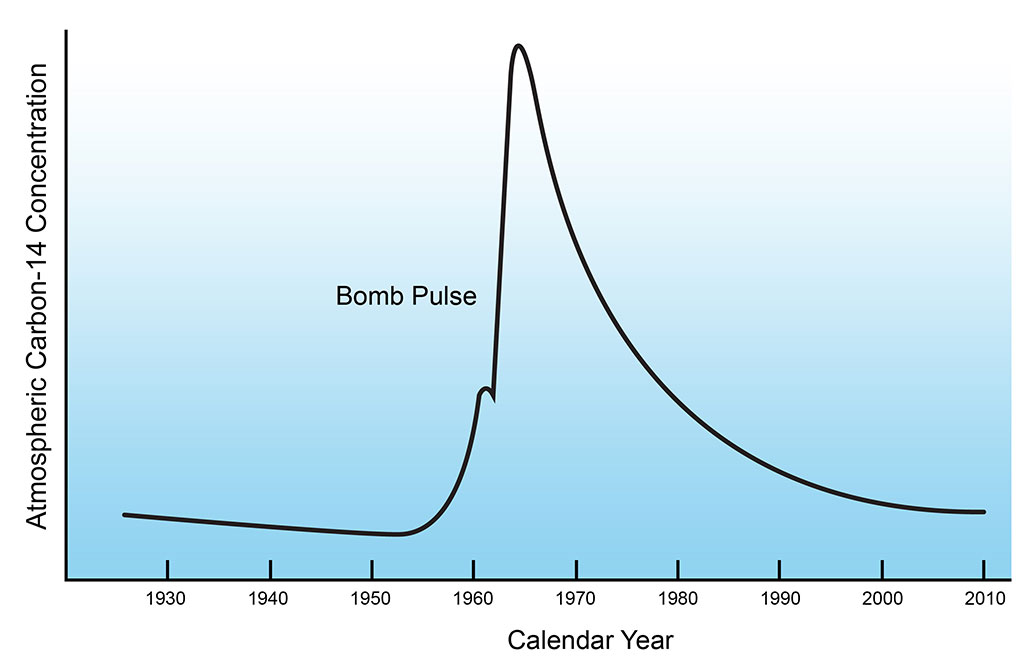

But all that changed during the middle of the last century. From the mid-1950s to 1960s, the U.S. military carried out a large number of above-ground nuclear weapons tests. (Thankfully, these tests ended in 1963.) Fallout from those nuclear bombs suddenly — and dramatically — boosted the amount of carbon-14 on or near Earth’s surface. It was like having a fresh source of carbon-14. A well-known graph of this has been nicknamed the “bomb curve.”

The sudden burst of extra carbon-14 from those bomb tests gave scientists a bookmark in time. After the tests, there was enough carbon-14 in recent things to be able to measure. Now, instead of using the natural decay of carbon-14 to date things, scientists now could use a change in the ratio of carbon-14 to stable carbon-12.

This ratio made carbon dating suitable for analyzing artwork, samples of tea, an unidentified body — or even a tusk of elephant ivory found in the back of a truck.

Scientists knew that the fallout’s carbon-14 signal wouldn’t last forever. As carbon cycles through living things, the share of this isotope would naturally fall over time. But new analyses show its usefulness is ending far earlier than it would have without recent growing emissions of carbon-based pollutants due to widespread use of fossil fuels.

The problem with fossil fuels

Fossil fuels such as coal and oil come from ancient organisms. Because they are millions of years old, they contain no carbon-14. (In fact, it’s all virtually gone within 50,000 years).

So by burning these fuels, people have been seeding the atmosphere with more and more carbon-12. This has diluted carbon-14 in the environment. The result is that the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 has been getting steadily smaller.

Heather Graven is an atmospheric scientist. She works at Imperial College London in England. Graven led the team that measured the effect of fossil fuel use on this ratio. That ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 acts like a time stamp for things that died after the weapons tests, she explains. If carbon-14’s share in something is higher than in similar items from before the Industrial Revolution (the early 1800s), “then you know this material is from the last 60 years,” explains Graven.

Her team now reports that this ratio has decreased far faster than first expected. In fact, it’s now back to the point it was at before the bomb tests.

What this means, she says, is that “the fossil-fuel effect is really taking over.” With every year, this carbon time stamp for dating relatively recent objects has become a little harder. It’s gotten to the point “where new things could look as if they were old,” she says. So scientists won’t be able to use it to conclusively date recent remains. Carbon dating could assign anything from a year old to 75 years old the same apparent age, Graven’s team reports.

Forensics and more could suffer

Bruce Buchholz is a chemist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. There, he has used the bomb curve to solve some basic biology questions. For instance, the carbon ratio has helped him determine which body structures (such as muscle) can repair themselves and which cannot (such as the Achilles tendon and lens of the eye).

He, too, has observed a drop in the reliability of carbon dating for relatively “young” tissues. Initially, that drop appeared to be just due to normal mixing of the bombs’ excess carbon-14 within the atmosphere and oceans. But in the last 10 to 20 years, he says, the problem with carbon dating increasingly has been driven by fossil-fuel burning.

Scientists are seeing — in real time — the impact that fossil-fuel burning is having on their ability to do good science. Explains Buchholz, “losing this technique might make a sample that’s contemporary [new] look like it’s from pre-bomb times.”

By the end of this century, Graven adds, the carbon-14 ratio will be equivalent to what it was 2,500 years ago.

Scientists have been able to use this technique to very precisely mark items from a very short, very recent point in history. Graven says that scientists knew carbon dating’s usefulness would be short-lived. But now, she says, her team has shown that it’s not something to expect in the distant future: “It’s happening now.”