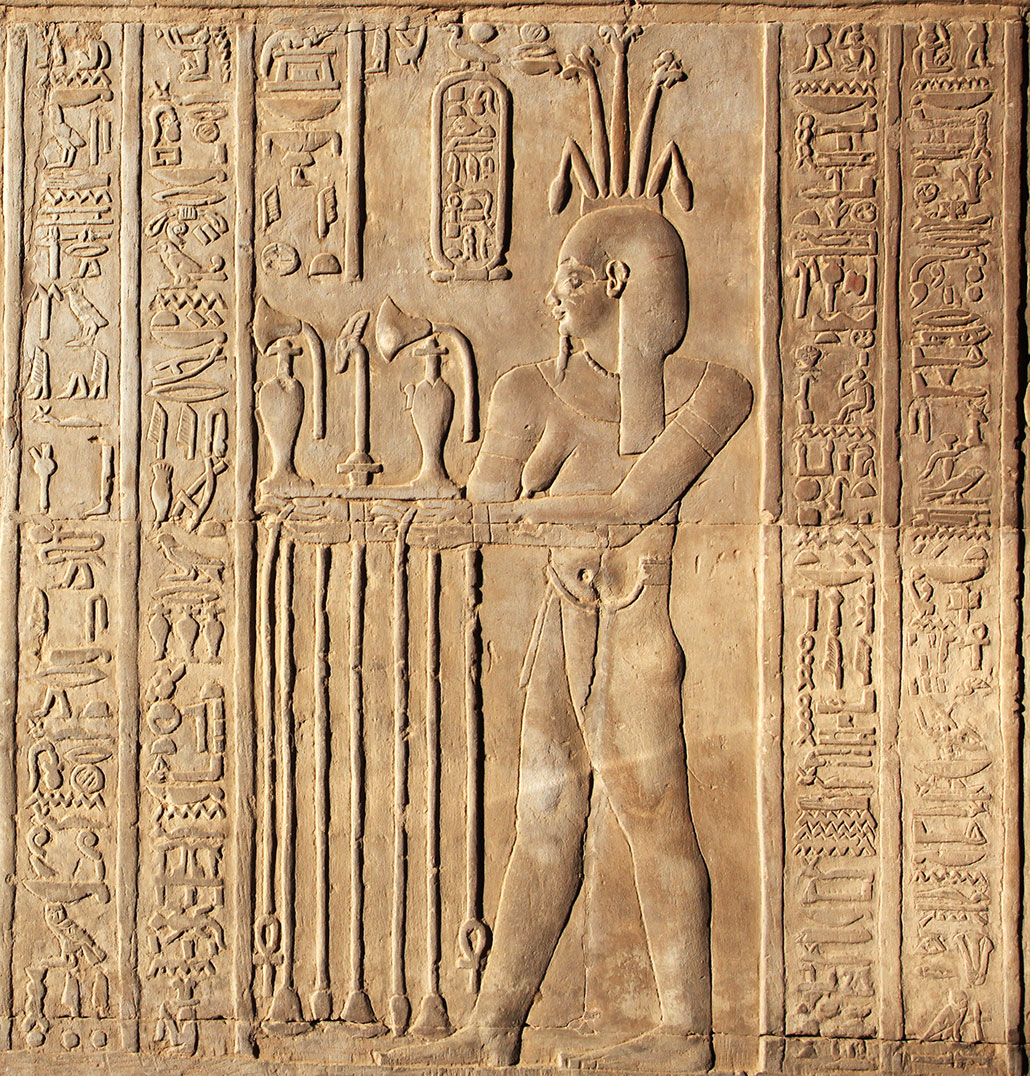

When he became Egypt’s king in 1145 B.C., Ramses VI faced a smelly challenge. The new pharaoh’s first job was to rid the land of a swampy stench. At least, that was the instruction in a hymn, or ceremonial song, written for the king’s rise to the throne. It begged the royal to remove the reek of fish and birds around the Nile River.

Those weren’t the only smells those ancients talked about. Texts that have survived until today mention whiffs of sweat and disease. Also, cooked meat, trees, flowers and incense. That last substance produces a sweet aroma when burned. And Egypt’s hot weather meant that people would have clamored for perfumed oils and ointments. Those substances could cloak their bodies in pleasant smells.

Maybe it’s no surprise that ancient Egyptians encountered a wide range of odors. “Written sources demonstrate that ancient Egyptians lived in a rich [scented] world,” says Dora Goldsmith. Goldsmith works at the Free University Berlin in Germany. There, she studies ancient Egypt. To fully understand its culture, she says, researchers need to really examine how pharaohs and their subjects experienced their worlds’ smells. No such study had ever been conducted.

Archaeologists usually study visible objects to understand how people lived in the ancient past. For example, researchers have learned what buildings looked like based on excavated remains. And they’ve gotten hints to how people lived by analyzing tools, accessories and other objects.

Rare projects have tried to re-create sounds from thousands of years ago. But ancient landscapes of scents — or smellscapes — have received even less attention. Ancient cities in Egypt and elsewhere have been described as “colorful and monumental, but odorless and sterile,” Goldsmith says.

Now change is in the air. Some archaeologists are sniffing out odor molecules from artifacts. Others are poring over ancient texts. From these, they hope to unlock perfume recipes and re-create their aromas. Such research aims to unveil the scents that permeated lives in the ancient world. And that may help us understand how people back then thought about their world.

A nose for molecules

Chemical analyses are allowing researchers to identify molecules that made ancient aromas. Molecular clues to scent have been plucked from cooking pots, debris from garbage pits and even mummies’ bodies.

Take the incense burner. Finding an ancient one indicates only that something was burned. But charred residues in them can reveal exactly what was burned, says Barbara Huber. Incense may have included blends of scented substances such as frankincense (FRANK-en-sense) and myrrh (Murr). Those spicy-smelling resins come from shrubs and trees. Figuring out what molecules made up an incense can help to reconstruct its fragrance, Huber says. An archaeologist, she works at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. It’s in Jena, Germany.

Huber was part of a team that did this sort of detective work on the Middle East city of Tamya. It’s in what’s now Saudi Arabia. The ancient walled city is thought to be a mere pit stop on the Incense Route. Traders traversed that network of pathways carrying frankincense and myrrh. But maybe Tayma was more than just a place for trade caravans to refuel.

Huber’s team has found that residents of Tamya had their own interest in scented plants. The people of Tamya purchased them for their own uses during much of the settlement’s history, her team found. The work analyzed charred resins there. Near the town wall, cone-shaped burners had smoldered with myrrh. Cube-shaped devices once burned frankincense in an area full of homes. And another aroma wafted from incense burners near a large public building. Those fragrances likely had special meanings that permeated Tamya. Huber’s group reported its findings in 2018. The team shared them at a conference in Munich, Germany.

Other researchers have also sought molecular clues to scent in museum artifacts. In Italy, analytical chemist Jacopo La Nasa works at the University of Pisa. His team studied 46 vessels, jars, cups and lumps of organic material from an underground tomb. That tomb was the resting place of Kha and his wife Merit. Though they weren’t royals, they were important. They lived from about 1450 B.C. to 1400 B.C. That time was during Egypt’s 18th dynasty.

Over the ages, substances inside the vessels had decayed. This decay released gases that the researchers analyzed. The gases offered a whiff of the original contents. The team used a type of mass spectrometer (Spek-TROM-eh-tur). That instrument identifies molecules based on their mass.

The leftovers stuck to seven open vessels and the one mystery lump pointed to oils, fats, beeswax or a mix. One open vessel yielded possible markers of dried fish and a scented resin.

The remaining containers were sealed and had to stay that way (due to museum rules). But sticking the mass spectrometer into the neck of those vessels provided clues to what they once held. From some objects, the team found signs of oils or fats and beeswax. Evidence of a type of flour appeared in one vessel’s neck. The scientists shared those findings in May in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Museum-based studies such as La Nasa’s might one day unlock ancient scents, Goldsmith says. But only if researchers can open sealed vessels and — with some luck — find enough telltale molecules to what the jars once held.

La Nasa’s group wasn’t so lucky, she says. “Their analyses did not detect any [specific] scents.”

Cleopatra’s perfume

Oils, fats and beeswax could have provided a base for adding scented ingredients. This was a common practice for making perfumes, Goldsmith says. Egyptian perfume makers would have started with a mix of those substances. Then they would have added fragrant ingredients. These could have included myrrh, juniper berries, frankincense, nut grass and the resin and bark from certain trees. Heating such brews made strongly scented ointments.

Explainer: What are fats?

Goldsmith’s research suggests that a tradition of fragrant medicines and perfumes began some 5,100 years ago — with the earliest Egyptian dynasties. Ancient writings describe recipes for several perfumes. But their precise ingredients and amounts remain a mystery.

That didn’t stop Goldsmith and a colleague from trying to re-create a celebrated Egyptian fragrance. Called the Mendesian perfume, it took its name from Mendes, the city where it was made. Cleopatra, who reigned as queen from 51 B.C. to 30 B.C., may have doused herself with this scent.

Archaeologists have been excavating the area near Mendes since 2009. They uncovered the roughly 2,300-year-old remains of what was probably a fragrance factory. They found kilns, used to heat materials to high temperatures, and clay containers for perfume.

After experimenting with ingredients including myrrh, cinnamon and pine resin, Goldsmith’s team produced a scent that they suspect is not far off from what Cleopatra wore. The long-lasting blend is strong but pleasant. It’s both spicy and sweet. Riffing off how perfumes are named today, the researchers dubbed the scent Eau de Cleopatra. A description of the excavation and efforts to revive the Mendesian scent appeared in the September 2021 Near Eastern Archaeology.

Goldsmith has re-created several other ancient Egyptian perfumes from written recipes. Such fragrances were used in everyday life. Ancient Egyptians would have used the scents for temple rituals and mummification.

Aristocratic aromas

Scented molecules and re-created perfumes can’t capture all the ancient world’s smells. For a more complete picture of a place’s smellscape, Goldsmith is scouring ancient texts for references to scents.

Here’s what a “smellwalk” through an ancient city could entail, she says.

Start in the royal palace. There, the perfumes of rulers and their family would have been overpowering. The sweet smells would perhaps have symbolized special ties to the gods. It would have masked the less pleasant scents of court officials and servants. Goldsmith wrote about this in a chapter of The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East. It was published in 2021.

Exit the palace and head to another spot in an ancient Egyptian city. Here, students learning to be scribes (writers who carefully copy text) would have lived in a special building. Achieving such knowledge required total devotion, Goldsmith says. These special writers were supposed to avoid perfume and pleasant scents. One ancient source described aspiring scribes as “stinking bulls.” That name speaks, and reeks, for itself.

Finally, go to an area filled with artisans. In workshops, sandal makers mixed chemicals to soften animal hides. Metal workers who made weapons sweated in front of furnaces. These craftspeople probably developed their own set of foul smells, Goldsmith says.

Stinky odors got far fewer mentions than sweet ones in the written accounts from ancient Egypt that Goldsmith reviewed. So streets were probably filled with funky scents that aren’t named in surviving texts. For instance, people raised goats and other animals that probably stank. And butchered carcasses, trash and open areas used as toilets got no mention.

Cultured noses

By reconstructing an ancient city’s smellscape — both the pleasant and the foul — researchers can try to figure out how ancients interpreted those smells.

Scent is a powerful part of the human experience. People can tell different smells apart surprisingly well. Today, scientists know that smells can instantly trigger memories. And meanings often get attached to specific scents. The smells of grilled hot dogs and freshly mowed grass bring memories of summer days at the ballpark.

Modern people probably perceive the same smells as nice or nasty as folks did in ancient societies, says Asifa Majid. She’s a psychologist in England at the University of Oxford. In line with that idea, members of nine cultures from around the world agreed with city dwellers in the United States when ranking how pleasant they found 10 odors. For instance, hunter-gatherers in the southeast Asian nation of Thailand agreed with people living in New York City. So did farmers living high in the mountains of the South American country of Ecuador. Majid and her colleagues shared their findings in the May 9 Current Biology.

Smells of vanilla, citrus and floral sweetness — dispensed by pen-sized devices — got high marks. Odors of rancid oil and a scent like ripe cheese or human sweat evoked frequent “yech” responses.

Maybe the ancient Egyptians living near the Nile River as Ramses VI took the throne experienced one big “yech.” That could explain the hymn about ridding the land of its smells of swampy fish and fowl. But Goldsmith argues that the hymn’s meaning is deeper. Bad smells may have been worse than annoying. Ancient Egyptians may have considered them evil and in conflict with sweet smells.

In 2019, Goldsmith published an analysis of texts written under several ancient Egyptian kings. She was struck by frequent references to scent-based standoffs. This was fairly new territory for researchers trying to understand ancient Egypt. She concluded that ancient views about good and bad smells could provide insights into how these people viewed their world.

Evil smells

For instance, researchers have long known about the ancient Egyptian concepts of isfet and ma’at. Isfet referred to a natural state of chaos and evil. Ma’at denoted a world of order and justice. These notions helped ancient Egyptians decide what was good or bad.

Specific odors were linked with isfet and ma’at, Goldsmith proposes. She wrote about this in a chapter of the 2019 book Sounding Sensory Profiles in the Ancient Near East. In Nile societies, the smelly fish and birds represented isfet’s nasal assault. Fish signified not only stench but also danger outside of the land that the pharaoh controlled. Meanwhile, ancient documents equated scented ointments and perfumes with the ma’at of pharaoh-ruled cities. Those places would have been considered civilized and therefore good, she says.

The pharaoh’s first duty was to replace the stink of isfet with the sweet smell of ma’at, Goldsmith argues. That meant both physically — in the odors that entered noses — and socially, by providing order for society. In his welcoming hymn, Ramses VI got a friendly reminder to make Egypt politically strong and fresh-smelling.

That’s an interesting idea that needs more investigation, says Robyn Price. She’s an Egyptologist at the University of California in Los Angeles. Price thinks that how people thought about specific scents has changed over time. For instance, some ancient texts describe the places where fish and fowl flourished as a place of divine creation. In that scenario, they would have been associated with the good ma’at. And ideas about smells pegged to an area may have been influenced by prejudices against those living there. For instance, texts from southern Egypt often spoke negatively about northern Egyptians. That may have influenced claims that northern marshes stunk of isfet.

The ancients may have tagged the same odors as pleasurable or offensive as people do today. But culture and context likely shaped responses to those smells, too.

Pharoah Ramses VI undoubtedly regarded his perfumed world as the best example of civilization. But in the air of city streets, Egyptians sandal makers and smiths would have lived in their own smellscapes. Though vastly different, these whiffs of the past each hint at how ancients experienced the world.